Most Afro-Latinos In America Identify As White Not Black – Study

A new study from the Pew Research Center is shedding light on the way some U.S. Afro-Latinos identify, and it may surprise you.

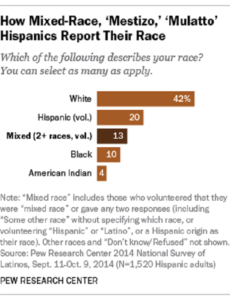

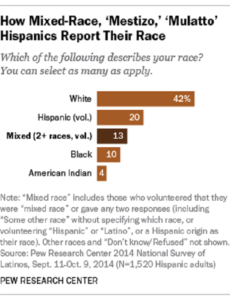

According to the survey, of the 24 percent of Latinos in the country who are Afro-Latino, just 18 percent of them identified their race as “Black.” In fact, researchers found that 39 percent of these African-descended Latinos called their race “white,” significantly higher than those who said “Hispanic,” 24 percent, “mixed,” 9 percent, and “American Indian,” 4 percent.

The findings reflect the complexity of Latino identity, which reflects a long history of indigenous, African, Asian and European mixing across the region under Spanish and Portuguese colonialism.

While the study might seem as evidence of Latinos’ push to whiteness as well as the community’s anti-blackness, it reveals as much, or as little, as it doesn’t. Researchers did not, for instance, share what questions were asked, how they were posed or to whom they were asked.

Researchers did, however, identify that most Afro-Latinos in the U.S. live in the South and/or on the East Coast, have Caribbean roots and have lower household incomes and education attainment than other U.S. Latinos, things we’ve known for a long, long time.

Comment (1)

Timothy Walker

The survey or article about Afro Latinos identifying themselves as white does not surprise me. The oppressed tend to take on the mind set of the oppressors with out knowing it. Due to white supremacy and colonizing people of color; people who have been colonized will identify themselves with the race they believe is in power. Slavery and the destroying of one’s history along with Europeans mixing with the colored races has caused a termination of one’s identity.Therefore; people of color such as the Afro Latinos will identify with people who they believe have ownership over the planet. When history says different, but because most people of color has an inferiority complex due to lack of knowing their history, the results will be that they will identify themselves as white when they are not.