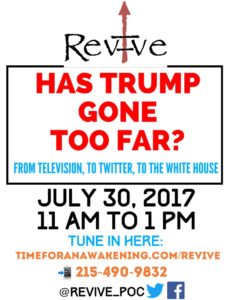

“Proof of Consciousness” (P.O.C) the Host of REVIVE!!! 7/30/2017

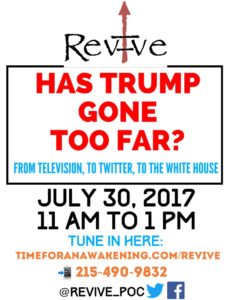

Today’s REVIVE show topic is entitled:

“HAS TRUMP GONE TOO FAR?!”

#Politics #LGBTQ

#TransRights

#Trump

I need you all to be apart of the conversation!

#Revive

#POC

It would be amazing to hear your perspective. So please call in we want to hear what you guys out there have to say always. Once again this show is for the people. We here at REVIVE thrive off of communication. So call us at (215)490-9832. This episode of REVIVE will be an open forum so all perspectives can be heard through great conversation.

This episode on REVIVE is entitled “HAS TRUMP GONE TOO FAR?!” Join us for this thought provoking conversation as we discuss this current administration and everything that has been done so far.

GUEST:

Susan Maasch: Susan Maasch is the Executive Director of the Trans Youth Equality Foundation. TYEF is a national nonprofit that advocates for transgender youth ages 2-18. Their mission is to share information about the unique needs of this community, partnering with families, educators and service providers to help foster a healthy, caring, and safe environment for all transgender children. The organization educates at medical and educational conferences, designs support groups around the country and trains schools. She is the proud mother of a transgender child.

Kyle Smith: Kyle Smith is a transgender youth that grew up being supported by TYEF. After being part of their programs for over 8 years, he now serves as Board Advisor. Kyle lives in New England and majors in Public Health and is an artist. While taking a year off of college he is enjoying designing and co coordinating TYEF’s first Trans Youth Arts Conference in Boston at Harvard University. This conference will use the arts to pull together transgender youth from all backgrounds and communities, with the premise that the arts build community, add beauty to our lives, reflects on our society, and encourages sharing,expression and healing.

Ray Gibson: Ray Gibson, is a 59-year-old Black transgender man, and a veteran of the United States Air Force. Ray is also certified as a public speaker. He has a Bachelor of Information Technology that he received in 2006. Ray has been in transition since 2012 and has continued to research transgender identity. Although retired, Ray continues to work as an advocate for transgender rights and racial equality. Ray is a mentor to men and women around the world and an in demand speaker.

YOU CAN CATCH REVIVE EVERY SUNDAY 11 AM-1 PM & EVERY WEDNESDAY 8 PM-10 PM!!!

It would be amazing to hear your perspective. So please call in we want to hear what you guys the listening audience out there have to say always. Once again this show is for the people. We here at REVIVE thrive off of communication. So call us at (215)490-9832 & follow on Twitter and Facebook @REVIVE_POC !

WE NEED YOU ALL TO BE APART OF THE CONVERSATION!!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 2:18:17 — 63.5MB) | Embed